- Circular Rising

- Posts

- Q&A: Blame the system, not the litterer

Q&A: Blame the system, not the litterer

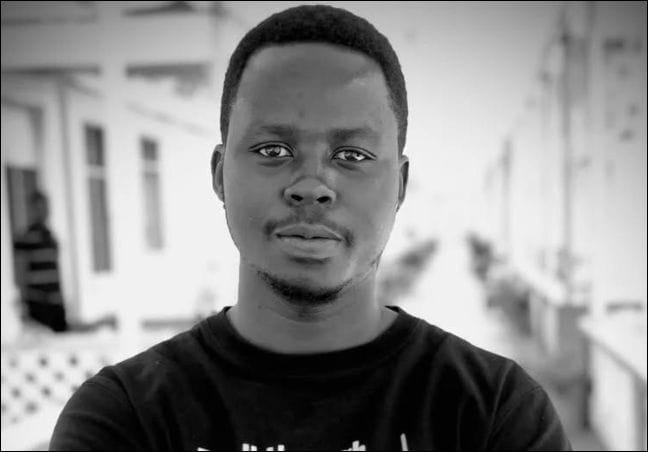

Source: Valentine Onditi

From the newsletter

While poor waste management is often framed as a behavioural problem, its true drivers lie in broken systems, says Valentine Onditi. He says in many African cities, uncollected trash and harmful practices like burning plastics are symptoms of underfunded infrastructure, fragmented governance and urban planning that has not kept pace with rapid growth.

Mr Onditi is a circular economy advocate and Head of Marketing at Jirani Recyclers Kenya, a waste management company that transforms polythene bags into meaningful products.

He argues that solving Africa’s waste crisis requires more than awareness campaigns or downstream recycling, calling instead for systemic change that tackles the root structural challenges.

More details

Drawing on your experience in Nairobi’s waste sector, what do you think is the most misunderstood issue about waste management in many African cities?

Valentine Onditi: I would say the most misunderstood issue about waste management is the assumption that the problem is primarily about behavior or awareness. In reality, it is fundamentally a system failure, not a moral one. People do not burn waste because they want to. They burn waste because it accumulates faster than it is collected, because collection is unreliable, unaffordable, or entirely absent. When waste stays uncollected for weeks in dense settlements with limited space, burning becomes a coping mechanism rather than a choice.

Waste collection is often described as the weakest link in the waste management system. Based on what you have seen in Nairobi and similar urban contexts, why does collection fail so consistently, even where policies and plans exist?

Valentine Onditi: Collection in urban cities fails for several structural reasons. For a start, urban planning has not kept pace with urban growth. Informal settlements were never designed for truck-based collection systems, narrow pathways, lack of access roads, and high density make conventional models unworkable. Then there are financing models that are misaligned with reality. Collection systems assume households can pay regular fees, yet a large share of urban residents live on informal or have unstable incomes. When payment fails, services collapse. Fragmentation of responsibility is also a major issue. Counties, private collectors, community groups, and national regulators often operate without coordination. We also have policies that exist on paper only, but implementation capacity is weak. Above all, waste is politically invisible. Collection is not a glamorous infrastructure and it rarely attracts the same attention as roads or energy, despite being foundational to public health and climate outcomes.

Informal waste workers handle a significant share of recyclable materials in Nairobi and in many African urban systems. What role should they play in a functional waste management system, and what is currently missing to make that integration work?

Valentine Onditi: Informal waste workers already form the backbone of recycling systems in Nairobi and I believe in other cities across Africa. They recover a significant share of plastics, metals, and organics long before formal systems intervene. The mistake has been treating them as a problem to eliminate rather than a system to strengthen. In a functional waste management system, informal workers should be recognized as legitimate service providers, organised into cooperatives or associations, integrated into collection, sorting, and aggregation, and compensated for the environmental services they provide, rather than only for the materials they collect. To achieve this, we need to address what is currently missing, and which includes formal recognition, stable contracts, occupational safety, access to infrastructure, and inclusion in policy design. Without these, integration remains rhetorical rather than real.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies are gaining traction in Kenya and across parts of the continent. From an operator’s perspective, how are these regulations influencing waste management on the ground, and what challenges remain?

Valentine Onditi: EPR policies in Kenya are a step in the right direction, but their impact on the ground is still uneven. They have begun creating new financing streams, supporting buy-back centers and aggregation, and bringing producers into conversations they previously avoided. However, there are challenges that need to be addressed. For instance, funds often do not reach informal collectors; focus is skewed toward easily recyclable plastics, ignoring organics and residuals; and governance of Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs) lacks transparency. EPR will only shift outcomes meaningfully if it pays for collection and sorting where waste actually accumulates, especially in low-income areas—not just downstream recycling.

Looking ahead, what would a realistic, functional waste management system for an African city actually look like, and what trade-offs will cities have to accept to get there?

Valentine Onditi: Such a system would not be a European model transplanted wholesale. Instead, it would be hybrid, incremental, and socially grounded. Key features would include universal basic collection, even if service levels vary; decentralized systems such as community sorting hubs, composting, and transfer stations; formal integration of informal workers as core actors. Additional features include EPR funding tied directly to collection and recovery performance; strong local governance and data, even if imperfect; and an acceptance that not all waste will be recycled, with reduction and redesign recognised as essential.

For trade-offs, cities must prioritise progress over perfection, inclusion over efficiency alone, and long-term system building over short-term optics. Ultimately, waste management in African cities is not merely a technical challenge, it is a development, justice, and governance challenge. Sustainable outcomes become possible only when systems are designed around how people actually live and work, rather than how policies imagine they should.